Not Knowing What You Know

Or, What Do You Mean You Don't Want to Read How a Murder's Really Investigated?

“I hope no one has snapped you up…yet.”

That was a query response I received many years ago from Janet Reid, a literary agent who sadly just passed away. Reid was best known as the QueryShark. She tore apart unfocused, rambling, incoherent, and bizarre query letters from writers seeking representation. Was notoriously brutal but well-intentioned. Aimed to educate the publishing-ignorant. Which I was—er, still am. She asked to read my novel. I sent it along, and waited for the bags of money to arrive.

A week later I received a long email listing all the ways the book was a failure. She identified problems with pacing, character development, plot, and pacing (she really leaned on that). Her most resonant advice? I had to account for the fact that readers have years of experience with how fictional investigations are conducted. I cared too much about portraying the real thing. Her notes were spot-on. The book was a mess. It took me three years and two more novels to get my first agent.

That experience was a necessary ego check. In my previous life I’d been a homicide detective with the NYPD and member of a federal task force. I was good at my work, and my work involved a lot of writing. I also consumed culture in buckets. I grew up an only child. Now that I think of it, I remain an only child. I read, watched movies and television shows. Noted what I responded to, what turned me off. Began sketching ideas for novels of my own. Started on one. It felt viable (it wasn’t; see above). I told my wife I wanted to retire and become a writer. Cop-knowledge hubris juiced me. Success was guaranteed; I did The Thing, who wouldn’t want to read me?

When Andromeda Romano-Lax approached me for a guest post (thank you!), she suggested I point out what writers get wrong about law enforcement. That’s a great concept, but not what I’m interested in. Since the Queryshark’s email, I’ve sold five short stories, won a (minor) award, landed a new agent, and co-wrote three television projects being shopped around Hollywood. All of that happened because I left my past behind.

Mostly.

There’s a long history of writers leveraging professional experience in other fields. Tess Gerritsen was a doctor, John Grisham a lawyer. Michael Connelly and John Sandford were journalists, and Isabella Maldonado and Joseph Wambaugh were cops. They all know their fields, and that informs—but doesn’t overwhelm—their work. And that’s an important distinction.

When I started writing, I leaned into my experience working murders. Snatched details from cases, worked them into my stories (hey, Dick Wolf’s been doing it for years). I clung to reality and embraced procedural minutiae. I included too much. Way too much. Plots buckled under the weight of Endless Detail. Characters? Hell, they were afterthoughts.

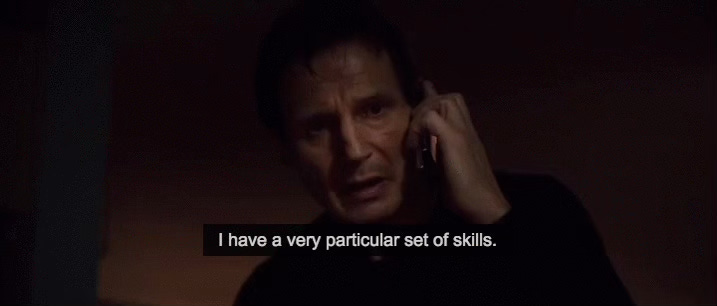

I rated my talents on false equivalency. Thought because I knew what a show like The Shield got wrong (very little—excluding the Armenian money train heist and ease of obtaining black market hand grenades), that I could do the thing better. Hollywood relies on technical advisors to add accuracy to military gunfights, legal thrillers, medical dramas. Basically any story featuring, well...

…but few technical advisors make the switch from assisting writers to becoming one. Zoanne Clack of Grey’s Anatomy is an excellent exception. It took me a while to realize in order to grow as a writer, I had to forget what I knew as a detective.

I had to stop being a cop.

Take Adam Plantinga’s tremendous debut novel, The Ascent. The story focuses on a former police officer guiding survivors through an epic prison riot; think Jack Reacher in The Poseidon Adventure. I’m using Plantinga here because in addition to writing, Adam’s also an active-duty San Francisco police sergeant. Procedural and technical knowledge is sprinkled into the story. But what pulls the reader through aren’t details about firearms or codified cop responses; it’s the characters. The novel’s got heart. Some even get torn from people’s chests (I’m exaggerating. Kinda.).

The classic advice is to write what you know. But that can be limiting. Even outright debilitating. Police culture is insular, especially recently. It’s easy to live in a bunker. Tunnel vision can limit what you find interesting and how you tell your story. Lack of scope held me back. It took me two three novels to write a non-cop point-of-view character. When I did, I was terrified. I knew detectives and criminals—occasionally they were the same person—who was I to take on a proper human?

Oh. Wait. I am one.

That bit about writing what you know? Scratch that. Write what you want to know. Talk to people who’ve lived different lives. Immerse yourself in places, cultures. Do the research—but do not let it consume you. I’ve been shocked at how many specialists are willing to talk about their professions. I’ve cold-emailed a lot of people. Many have responded. I’ve even built a few friendships. In short, I’ve widened my imagination’s aperture.

I think a lot these days about resonance. What stories I think about long after I’ve finished reading. I devour clockwork mysteries from writers like Clare Mackintosh (another former police officer; my thesis is getting shot to hell) and Anthony Horowitz. They are masters of storytelling. But—and this is no knock on them—their airtight plot machinations leave me soon after I finish.

These days I care more about emotional truths. Loaded phrase, that. Hassan Minhaj recently caught flak for portraying experiences that didn’t actually happen to him. That’s not to say I don’t care about accuracy—I do. But there’s a target in fiction and drama, however small, that nails the crossover between technical knowledge and gut-punch emotional resonance. Judge Holden’s scientific/religious/philosophical musings in Cormac McCarthy’s Blood Meridian. Ann Patchett’s use of medical science to flesh out State of Wonder. Hilary Mantel’s exhaustive research of Henry VIII’s court in the Thomas Cromwell trilogy. And Will Graham realizing the connection between murdered families in Michael Mann’s Manhunter (based on Thomas Harris’ Red Dragon).

All those works were thoroughly researched. They have that sense of verisimilitude. You may not know 18th century seamanship, but Peter Weir’s Master and Commander: The Far Side of the Earth just feels right. If a writer can pull a reader to that point, that place of “I’m with you” acceptance, they’re golden. Don Winslow once told me, “Just tell the story.” I wrote that on a Post-It and stuck it to my desk. Just tell the story.

Before my current agent took me on, he read my latest work. He loved the three main characters, their arcs, the description of early 1990s New York City, and “the cop stuff too” (he also complimented my portrayal of a ketamine high; which felt great, considering I’ve never even had a drink). His response moved me. Meant I’d evolved. I wasn’t just a former detective; I’d become a proper writer. I’d grown. Because I was able to let go.

That novel’s out with editors now. I’m hoping it sells and you’ll read it. If you do, and you find any factual inaccuracies, feel free to email me.

No promises that I’ll read it, though.