Welcome to 2024. Feels the same, no? Probably because time is a construct. But that’s too heavy a start to this newsletter.

As the clock rolled into a new year, I found myself thinking again of Tony Cornwell. Don’t recognize the name? You’re not alone. Tony is the older brother of David Cornwell, known to the world as John Le Carré, one of the 20th century’s great novelists. As revealed in A Private Spy, a collection of Le Carré’s personal correspondence, Tony was also a writer. As late as 2012, well into his eighties, Tony was still seeking his brother’s wisdom on the craft. Le Carré indicated he and his wife would provide editorial support, but more in the realm of clarity and comprehensibility than character or story. The tone of Le Carré’s response feels decidedly cool, almost hands-off. It makes the reader think the famous author has little interest in assisting his brother. But the younger Cornwell sibling had already helped the older. Or tried to, at least.

In 1994, Le Carré had approached Sonny Mehta, the then-head of Knopf and an industry legend, about acquiring Tony’s novel Born of the Sun. Mehta passed on the project and Tony died in 2017, an unpublished, forever-aspiring writer (but apparently a better-than-average cricketer). His decades of effort produced exactly zilch. And now he’s dead.

Happy new year.

In all seriousness, I think about Tony Cornwell a lot. I picture him, an elderly man in the winter of his life, hunched over a computer (or typewriter, or maybe a notebook; Le Carré wrote longhand), thinking, hoping, praying, “This is The One”. But in the end none of them were. And I wonder if, in those final moments, Tony thought all the hours spent alone, writing words nobody will ever read were a good use of his time on earth.

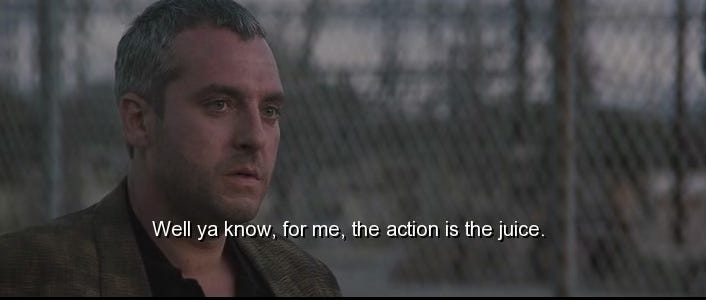

An optimist (and my therapist) would say yes. That the process is the reward (fans of Michael Mann’s Heat know this).

And I get that. I do. There are times I come away from a 1,500-word day with a sense of accomplishment. I feel lighter, because an unfinished project still has potential. A work-in-progress is Schrödinger’s novel: it’s alive, it’s dead. Neither state is definitive because, as Natasha Bedingfield taught us, the rest is still unwritten. So the optimist (and my therapist) would argue Tony Cornwell’s life was well-lived.

Problem is, police work produces few optimists.

If Tony Cornwell hadn’t been John Le Carré’s brother, would anyone know he was a writer? How much time did he spend, pre-dawn, or in the late hours, pounding away at his craft? Did anyone know? Did anyone care? One question nags at me: how important is outside validation?

For me, and I think for most others who create, the answer is very.

My wife has launched two companies and is starting a third. Her success enabled me to retire from the NYPD at age 42 to write full-time. We moved to New England and made new friends, one of which is an entrepreneur running a sizable company. A couple of years ago, my wife and I were at lunch with this woman and her husband. The subject of pickleball came up (shoot me now I’m so old), and this friend tasked me with learning the rules of the game because, as she said, I’m retired. It’s not like I’m doing anything else.

The hell I’m not.

Since 2018 I’ve written five novels, eight short stories, and co-created three television shows (pilot scripts, character profiles, show bibles, season arcs, and pitch decks). I write five to six days a week. And most working writers do. Walter Mosley writes three hours a day, every day. Every day. War historian James Holland works from 6 a.m. until past sunset. Don Winslow told me writing is a J-O-B job. Get in the chair and do the work. However hard, however long it takes.

So I have. And I wrote for years before I left the NYPD, both for the Department and myself. But outside of the four short stories I’ve sold and the newsletter you’re reading, you wouldn’t know it. And there are countless writers and creatives like me, working on flash fiction, or fan fiction, or a short story, or their spec script, or their YouTube channel, or their street photography, or landscape photography, or their TikTok, or their podcast (I’ve taken two swings at that), or their painting, or whatever. And nobody, outside of their closest friends and family, knows about it. Creative work is lonesome. It is difficult. And it often goes unrecognized, like our friend Tony, laboring away in his famous brother’s shadow.

Which brings me back to The Master.

Le Carré is very important in my life. He taught me genre fiction can be literary. But his impact goes beyond that. Not only was Le Carré an excellent writer of espionage, gifted with incredible insight into the psyches of men who betray and deceive, but he himself did the thing about which he wrote. In the sixties Le Carré worked for British intelligence. He was, in a misused term, a spy, and a contemporary of British double agent Kim Philby (the inspiration for Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy’s Bill Haydon). Laugh if you want, but I always aspired—er, still aspire—to bring that type of institutional insight to crime fiction. Winslow wrote his Border Trilogy based off intensive research and countless interviews. Michael Connelly’s Harry Bosch and Renee Ballard are creations inspired by Connelly’s relationships with LAPD detectives. I have spent countless hours in windowless rooms with people in their lowest moments. I like to think I’ve learned a little about human nature. When it comes to novels, I aim to cut out the middleman.

And at the start of 2023, at 46 years old, I thought I was on the verge of doing just that. I had a respected literary agent. One of our TV projects was generating serious heat. But things didn’t work out. I don’t know if this setback’s temporary, but I can’t help but feel the momentum slowing. I’m nearer to fifty than forty and recalibrating my metrics for success. This Substack is part of that effort. I want to learn how creatives measure the impact of their work.

Because, you see, right now, somewhere in the world, there’s another Tony Cornwell, actually thousands of them, working hard on their craft, hoping they are building something that will make it into the world, that will be seen and by being seen, provide proof of its creator’s existence, of their time on this planet. That they were present.

And though Tony didn’t get published, he tried until the very end.

We should all be so strong.

Oh, all of the feels here - time spent pouring words out over paper, fingers dancing over the keyboard. But I have come to find (at this ripe old stage of life) that it is worth it… knowing that work I've done is out there, regardless of who reads it… it is enough. I'm still writing. Still creating. Still an active participant in my own making.

And as le Carre once penned, “There is no such thing as a secure writer: every novel is an impossible mountain” that mountain could be anything - a writer’s block - should you believe in them, hesitancy on sharing, editing, impostor syndrome, trying to get published, attempting to make sales - it's not just one mountain…. It's a range.

I can't stop thinking about this piece--about persistence, "success," goals, what it means to be a creative and a writer...when to keep pushing and when (and if!) to ever call it. Phew! This is intense, Det. Allison!!