In 2007, John Maloof found himself at another storage unit auction. Maloof was an estate agent who frequented flea markets in search of collectibles. At the time he was working on a book about Chicago’s architectural history, and hoping to find photos to support the project. He blind-bid $400 on a box he could not open. Think Storage Wars, but with less “yeeeeeeeeeeup!”.

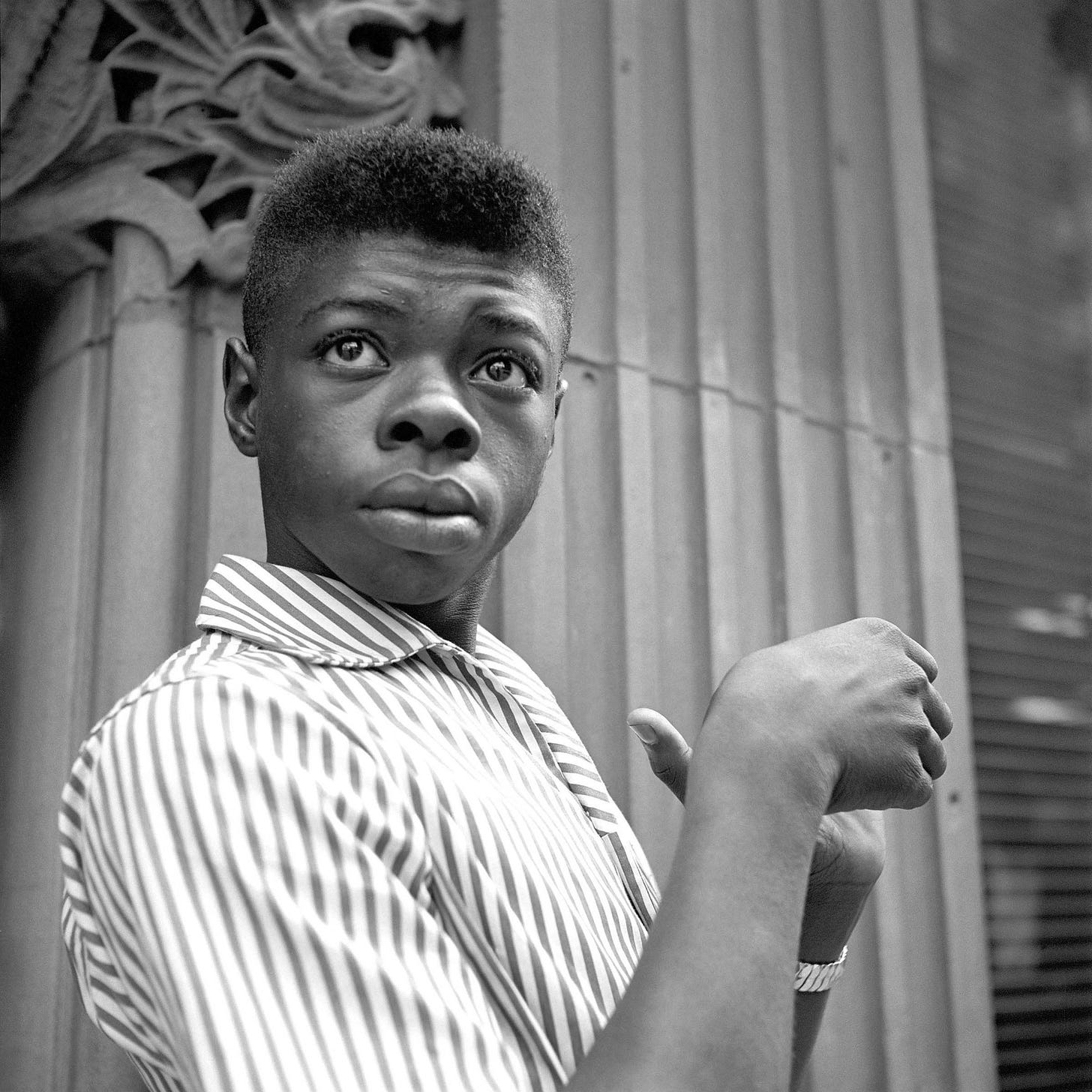

Maloof won the auction but was disappointed in the box’s contents. The negatives were not images of Chicago-area buildings or homes. They were black-and-white photos of everyday people captured in raw and unguarded moments. Initially Maloof didn’t give his haul much attention. But a few years later he began scanning the negatives and posted a few to Flickr, a photo-sharing site.

The images went viral, and the world was introduced to the work of Vivian Maier.

Maier was a professional nanny and housekeeper—and an enigma. The children she cared for have described her as either the ideal guardian or a stern disciplinarian. She died a few years after Maloof bought that first box—she was in a nursing home and had missed payments on the storage unit—but the creator and purchaser never met. Realizing he was sitting on photographic gold, Maloof tracked down more of Maier’s work. He now owns hundreds of thousands of negatives, prints, rolls of undeveloped film, 8mm films, and audio recordings. In the years since, he has become the caretaker of one of the most important collections of street photography in history.

And we don’t even know if this is what Maier would have wanted.

She did not show or publish her work. She never married, had no children or, apparently, friends. Those she worked for describe a politically-aware, emotionally withdrawn, intensely private person. Who also liked to take photos. A lot of photos.

But thanks to Maloof, she has since become the subject of books, documentaries, and critical examinations. Her work has been shown in galleries around the world. Paris named a street after her. Maier is now regarded as one of photography’s greats, up there with Cartier-Bresson, Diane Arbus, Elliot Erwitt, and Bruce Gilden. You can see why.

I’ve been fascinated with Maier’s work and story since learning about her ten years ago. Like Maier, I’m an avid photographer, though I don’t take photos of strangers like she did. Many of her subjects are looking toward the camera, but slightly above it. These images are unusually intimate. This is because Maier mostly used a Rollieiflex twin lens reflex camera, which is held at waist level. Maier’s subjects are looking at her, but Maier’s camera is looking at them.

Like Maier (I assume), I derive a quiet pride from making compelling images (though mine don’t come close to hers). And you know straight away whether your work is good. Writing can take months or years to produce a finished novel. Photography provides instant feedback; either you got the shot or you didn’t.

Unlike Maier, I can share my work on social media or host images on my personal website (I’m open to sponsorship possibilities, Squarespace). But Maier confined her work to her spare quarters in the upscale homes owned by her employers. It’s conceivable that, until Maloof popped open that box, no one but Vivian had seen her work. Some might find this sad. I find it empowering.

As I wrote in an earlier post, art should be created by the artist, for the artist. That was clearly Maier’s approach. Question is, was it by choice? If Maier lived in our time, would she have been hashtagging #streetstories and #twinlensreflexcamera? Maybe. Maier made many self-portraits, often depicting herself obliquely, in the corners of frames or layered in reflection. She inserted herself into her work, and by doing so, inserted herself into the world.

So, yeah, she might have done it for the Gram. But then again, maybe not. The beauty and tragedy of Maier’s story is we’ll never know. And that allows us to overlay our desired narrative onto hers. I refuse to imagine Maier as a frustrated, unrecognized genius.

I like to think instead that she was that purest of beasts, a creative for whom creation was the alpha and omega. Would she have welcomed acclaim? Possibly. She had to know she was good; her aesthetic reveals vision and taste. Was she constrained by the 1960’s limits on gender and class? Again, maybe. Maier was a nanny—a servant—and a woman. Did she rage nightly at the uncaring world, convinced it did not value her genius? Again, it’s possible.

Or, was she content in reviewing her images alone, analyzing which worked and why, striving always to do better the next time?

That’s the Vivian Maier I choose to believe in. And I’m envious of her.

Our brains and culture have been scrambled by the platforms provided by the internet. Everyone can be famous, or at least popular, at least theoretically. Just do what others do, imitate and recreate. Enslave yourself to the algorithm. Sell your soul for likes. Last night I posted five new images to Instagram. As of this draft, they have amassed a grand total of six seven likes (I revised this post this morning).

As Derrick Coleman once said, whoop-de-damn-do.

Social media offers incredible opportunity to share our work, but the results usually disappoints us. I’ll never be as famous (or as good) as Alan Schaller. And the constant striving and comparing and failing can, over time, wear one down.

There is a better, saner way. We can ignore the noise. We can be like Vivian Maier, going out day after day, putting the work in. Focusing exclusively on the next image, the next novel, the next painting. Doing it again, and again, and again, expecting nothing except maybe to do the thing a little better. And after a lifetime, you may have produced a body of work that will be admired by generations to come.

Thing is, you won’t be around to know it. Accepting that brings total freedom.

And who knows? Maybe one day someone stumbles across your manuscript, your hard drive, those poems you buried in your basement, and your work finally finds its audience.

Hm. On second thought, you might want to throw a selfie or two in that box.

Just in case.

All images made by Vivian Maier, ©Maloof Collection, LTD.